Don’t be a Dapper Danny

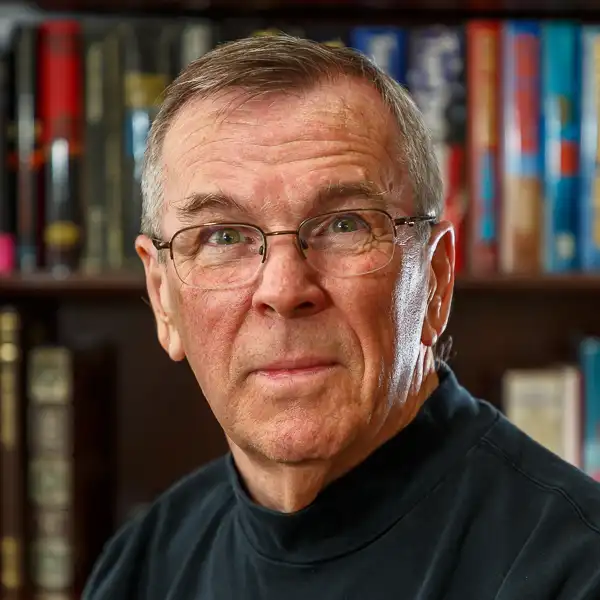

By Oliver Cummings

“Make hay while the sun shines” describes a farmer’s reality.

The sun came up hot on hay-bailing day and the dew was off the grass very early. By 8:00 I was throwing up wind rows of hay mown two days earlier and left to cure in the field. The side-delivery rake was just the right tool to pull behind the little red-belly Ford. Dad wasn’t far behind on the John Deere, pulling the bailer that produced 70-pound rectangular bales of alfalfa hay that would feed the cows and horses come winter. As the morning sun climbed the scent of the new mown hay gave way to the smell of dust kicked up by the raking and baling processes.

About 9:30, Johnnie and his hay-hauling crew pulled into the field. A couple of days later, we would move the whole operation to Johnnie’s farm to take in his hay crop, too.

Johnnie’s crew was his son, Jerry, just turned 17, Danny, one of Jerry’s high school buddies, and Bobby a 14-year old buddy of mine from school. All three were buff; strong. Jerry and Bobby, farm boys, a little rough around the edges. Danny was slicker, a town boy.

As they pulled into the field, Jerry and Danny dove off the wagon and started walking alongside the vehicle, now crawling along between two rows of bales. Jerry picked up a bale by the seagrass strings that bound it. He walked it to the wagon and heaved the bale up to Bobby, ready to start meticulously laying out the stack so the loaded wagon could move across the rough field without the load shifting. By the time Bobby got the bale positioned, Danny pitched the second bale on the wagon from the other side.

This ritual was repeated, with Bobby placing bale upon bale overlapping the so that one layer locked the next layer in place until they had five layers high and a tie-bale row down the middle, the length of the wagon.

Now they were thoroughly soaked with sweat, covered in hay dust, and ready to make the slow ride from the field to the barn, hoping for a breeze along the way. Johnnie turned the tractor over to Jerry to drive the half-mile to the barn for unloading and started walking home. He would be mowing the rest of the day on his own property a mile away.

The barn was a large central hallway flanked by stalls on either side. The hayloft was the second floor covering the main hallway and the internal stalls. It was cavernous today because last year’s hay crop had been almost totally fed out.

Jerry and Bobby climbed into the hayloft to carry back and stack the hay. Danny had volunteered to pitch up the bales from the wagon. With a light breeze at his back the outside work wasn’t too unpleasant. He would pitch a bale onto the hayloft floor; Jerry would hook it with the hay hook and drag it back to Bobby to stack. The hayloft was hot and stuffy.

All went well until the load was about two-thirds in the barn. Danny bucked a bale up and, more or less, pushed it into the door to the loft. With that, Jerry said, “Don’t strain yourself, Danny Boy.” Danny shot him a look and said, “Hey, I gotta go to the toilet.”

Jerry, short curly red hair glistening with sweat in the sunlight, jumped down onto the wagon and started bucking bales up for Bobby, now having to both drag back and stack. By the time Danny finished his toilet visit, the other boys had the wagon unloaded and were ready load number two. Danny trotted out to the road and jumped onto the wagon as they headed to the field. It was going on noon.

The second load went much as the first until half way through the unloading process, Danny got something in his eye and had to go to the house to see if Mom could get it out for him.

On the third load, it was a splinter in his finger that disabled poor old Danny, yet again.

Danny was a “goldbrick,” a slacker. Johnnie tolerated Danny on the crew because he was Jerry’s friend. But, when it came time for Dad to put a crew together to help Johnnie, Danny was not among those considered.

Goldbricks in Business

In the business world there are many ways that people exhibit slacking behavior.

Cyberslacking applies to employees who use company Internet connections and time for personal activities. However, there is a more subtle form of goldbricking in business that is a problem for managers and may result in personnel actions that the goldbricker may not expect.

As a young manager I hired a clearly talented person, I will call her Malinda, to evaluate training programs. In the first year she quickly became a good on-site evaluator.

I noticed, however, that on courses where she had some apparent investment (e.g., personal interest in the subject matter) she did a superior job. But, on assignments where she perceived the content to be boring, or the client to be “difficult,” her work output and the clients’ ratings of project quality were significantly degraded.

Over a period of three years Malinda’s performance was up and down, from excellent to below average.

I documented and discussed her performance on a project by project basis, summarized it during mid-year and annual reviews, and discussed it in career coaching sessions with her. The behaviors, however, persisted in a pattern that became predictable.

Toward the end of her third year, in spite of the negative feedback and coaching I had given her in the various venues, she apparently expected to be considered for a project lead position in the department. When I told her she would not be considered for the position, and that her performance was too inconsistent, she acted surprised and offended. Shortly thereafter she resigned, “to pursue other interests.”

The moral of the story.

Every employee needs to have some expertise that they are “known for.” This is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for being really successful in a career. To be successful on a job you must also be known as a steady performer, willing to take on every assignment with a clear intent to do it to the best of your ability.

Never miss out!

Get an email update every time I publish new content. Be the first to know!