Cholera Ghost Map

By the mid-1800s London was a crowded, smelly city that killed many of its residents. Well, to be more accurate, cholera killed many people living in the heart of a great, growing city.

We know today that cholera is an intestinal infection that leads to severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, killing its victim in days. It’s generally caused by infected water but in the mid-1800s the real cause was unknown. (Pasteur would not announce his germ theory until 1861.) The leading public health authorities of the day considered “miasma” (fetid air) to be the cause.

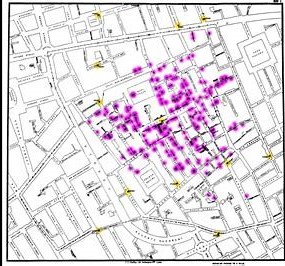

In August of 1854 London experienced another cholera epidemic, this time in the Soho district of the city and centered along a section of Broad Street. Within three days 127 people died of the disease and all of them lived on or near the street. The epidemic eventually killed about 600 people, but Broad Street was the epicenter. Why Broad Street and how did John Snow, an unknown physician, use data to solve the problem?

Edwin Chadwick was the leader of the General Board of Health for London, and he “knew” that the disease was carried in the unpleasant, smelly air of the city. The area was poor and overcrowded and because the new sewer system being built in the city had not yet reached Soho, the “water closets” in the buildings either emptied into a cesspool in the yard or the basement. Because of the poverty in Soho these cesspools were not cleaned out as often as required.

Dr. John Snow

Snow, however, was intrigued by the pattern of cholera death surrounding the thirteen public wells. Specifically, Snow mapped the deaths and found a cluster around the Broad Street pump. He identified the addresses of the victims and marked them on a map of the city. He was convinced that the Broad Street pump was the source of whatever was causing cholera.

In today’s terminology, he was not looking for causation, he was looking for correlation. And he found convincing evidence by using “small data,” 600 points on a map.

Overcoming obstacles from higher authority, he removed the pump handle from the well, forcing people in the area to get drinking water from another well. The epidemic was over and later they found the culprit, an old, leaking cesspool that was three feet from the well that residents used for drinking and cooking.

Lesson

To quote some of my six-sigma friends, Let the Data Speak! Sometimes the correlation leads to an educationed guess at causation.

Application

Whenever possible, use data to support your decisions. Opinions are just that, opinions.

Note: If you want to read a riveting story about the epidemic, I suggest that you get a copy of Steven Johnson’s wonderful book, The Ghost Map. It’s a great story.

Never miss out!

Get an email update every time I publish new content. Be the first to know!