What It Takes to Be A Facilitative Manager – Part 4: Foster Trust, But Not Too Much

By Oliver W. Cummings

4-17-2020

This post focuses on the fourth of the things beyond using good foundational management skills that the facilitative manager will do.

- Believe, but not too much

- Care, but not too much

- Feel, but not too much

- Foster trust, but not too much

- Have something you can’t have too much of: Integrity

Each of these balancing acts is important to establish and enhance your working relationships with your subordinates.

Foster Trust[i]

The trust developed between individuals should be (and usually is) based in part on the circumstance and in part on the specific experiences within the relationship.

In a management relationship, what counts as trust, how much trust is healthy, how trust is damaged and what must be done to recover from a damaged trust relationship are all issues of importance.

As you strive to drive relationships higher in the Manager’s Relationship Hierarchy achieving trusting relationships is pivotal.

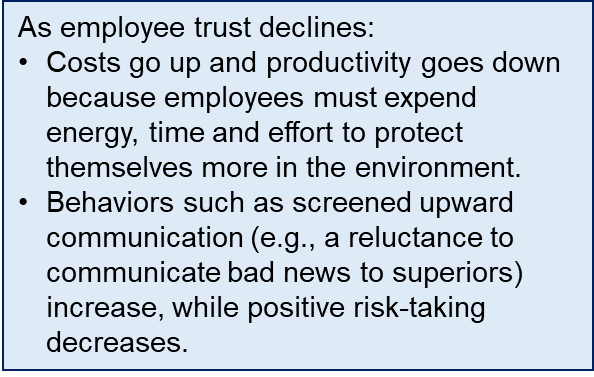

The failure to achieve an optimal trust level with an employee, co-worker, or client seriously limits your ability to collaborate, inspire confidence and achieve any acceptance of a mutuality of interests. Lack of trust limits effective cooperation and communication, decreases cohesiveness in the organization, and increases the complexity of transactions and exchanges within the organization.

Trust involves an individual’s recognition and acceptance of their dependence on someone else and is the manifestation of their control of that dependence.

The more dependence one person has on another, the more vulnerable they are to that other person’s decisions and behavior. Trust is bolstered by a sense of assurance that one will not exploit that vulnerability.

Early in a relationship trust is generally based on cultural and organizational structures and formal sanctions that are designed to deter untrustworthy behavior. For example, an employee can be confident that labor laws apply and that the company hierarchy or human resources functions will provide some protections. As a manager, you have a similar set of structures, policies and rules upon which to rely.

But very quickly, trust becomes based on direct knowledge and experience. Research has shown that with continuing contact, the level of trust between individuals changes little after 18 months of a relationship[ii]. Therefore, the first months of a manager’s various relationships are critical.

During these first months, you need to initiate and sustain increasingly fine-grained levels of trust with your employees, peers or superiors. Here are some keys to developing trust.

- Be predictable. A key to cultivating trust is consistency of behavior. Exhibit unpredictable behavior and you invite others to rely less on you and to build in protections against your variable behaviors.

- Tell the truth and keep your promises. Getting caught in a lie or breaking a promise will do immediate and usually long-lasting damage to your trustworthiness.

- Show concern for employee’s and other units’ rights and issues. Such concern provides a sense of security that you will not take advantage of the more vulnerable person in the situation.

- Be accurate and forthright in communications. To the extent you ethically can, you should provide adequate explanations of decisions and actions and provide open and timely feedback to employees and other co-workers.

- Share some control. Participation at a decision-making level with employees is effective. Learn and use effective delegation techniques to leverage yourself and inspire your staff at the same time.

- Demonstrate your competence. For others to trust you they must first believe you are competent (to do the job, to make the decision, to exercise sound judgment, etc.). If you are not competent you cannot be predictable, reliable, and accurate – in other words, you cannot be trustworthy.

Trust is fundamental to cooperation. It is pivotal in establishing relationships that transcend the ordinary work-for-a-paycheck mentality and move the relationship onward to levels of confidence and mutual commitment.

Optimum trust is regulated by several factors, including the particular situation and how critical the interdependencies are to individuals’ mutual success, the relative power of the individuals, past experience of the participants with each other, and the opportunities each participant has to use sanctions on the other for transgressions or betrayals.

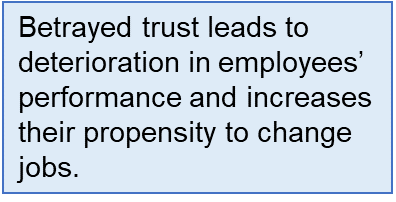

A number one rule is, “Do not betray a trust.”

What you are likely to hold high as a manager in deciding about trusting employees (competence, and reliability) is different from what the employees will care most about in judging you (integrity, benevolence and openness). What they see in you will be magnified and remembered more clearly than what you see in them. You are always on. You are a role model and your behavior and attitudes always count.

But Not Too Much

And, I should add “Not Too Little.” Remember, trust is a two-way proposition and that blind trust (that is, too much trust on your part) is an invitation to opportunism on the employee’s part. Too little trust in either direction in the unit can lead to suspicion and a propensity to protect one’s self in unnecessary and unproductive ways. Both conditions set the stage for failures in your unit.

You need to be trustworthy, but so does your employee (or your supervisor or client). I am reminded of President Reagan’s admonition to “trust, but verify.” You must always exercise your management responsibilities to plan, organize, measure/monitor, and make adjustments as needed for the best interests of the unit and your parent organization.

Next time: Integrity

What do you look for in your staff members to satisfy yourself that they are trustworthy?

[i] This post is based in part on a review article: Tschmannen-Moran, M. and Hoy, W. K. (2000). A multidisciplinary analysis of the nature, meaning, and measurement of trust. Review of Educational Research, Vol. 70, No. 4, pp 547-593.

[ii] Gabarro, J. J. (1978). The development of trust, influence, and expectations. In A. G.

Athos & J. J. Gabarro (Eds.), Interpersonal behavior: Communication and understanding n relationships (pp. 290-303). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.